The first entry in this series focuses on characters making a deliberate attempt to attack and injure an opponent.

I hope it can achieve these goals by collating all of the modifiers that you’re already taking into account in attack resolution and making them a more explicit part of the process.

A reminder (from the earlier post) of the four goals I’m trying to achieve:

- Make combat a more compelling storytelling experience.

- Have combat better reflect player choice in action and equipment selection so that it doesn’t feel disconnected and random.

- Make combat gameplay more engaging by expanding tactical outcomes and choices.

- Don’t add undue complexity or slow down the game.

System Summary

Here’s the TL;DR:

- Before an attack roll, the DM gathers all of the evidence (all the modifiers).

- Make the attack roll. Held against the evidence, it will either be a hit or a miss.

- The DM may associate the outcome of the roll to a specific modifier when describing the results to the players.

- Optionally, there may be gameplay implications from this that result in tactical changes to the combat.

The Call to Arms

“I attack.” “Roll to hit.” “I rolled a 17.” “You miss.”

How boring! And yet this has been my experience for most RPG combats, tabletop or computer-based. Maybe the GM adds a little color (“she dodges your sword swing”), but there’s very little of the context of what is going on in the battle to make it compelling. So I went to see what the ol’ Egg of Coot had to say:

During a one-minute melee round many attacks are made, but some are mere feints, while some are blocked or parried. One, or possibly several, have the chance to actually score damage. For such chances, the dice are rolled, and if the “to hit” number is equalled or exceeded, the attack was successful, but otherwise it too was avoided, blocked, parried, or whatever.

– Gary Gygax, 1st Edition AD&D Dungeon Master’s Guide, p.61

It was this “avoided, blocked, parried, or whatever” that got me thinking: we could quantify the “whatever” part here, and that would make things a little more exciting. By quantifying it, we could even make reasonable inferences that the players could understand and affect the tactics of the combat:

“He attacks. (rolls an 8) You deflect the ogre’s tree trunk with your shield, knocking you back one hex and putting him off balance.”

“Do I get a bonus since he’s off balance?”

“I’ll give you +2 to hit.”

“I move back in and attack with my sword. Ah crap, I rolled a 6.”

(looks at notes) “Your thrust was true, but you underestimated ogre leatherwork. Your sword is unable to pierce its cuir bouilli chestpiece.”

While we could write this off as colorful DMing, we actually have enough information to make these cause-and-effect rules. We’re still relying on random numbers via dice rolls to drive events forward, but we’ll organize our bonuses and penalties to inform what actually happened.

The Tug-of-War

I knew there was something in this idea, but I had to step back to fully grasp how it fit together. Here’s how I approached it:

First, I took a look at how we’re modeling combat. AD&D uses a 1-20 roll as the possibility space:

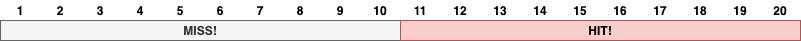

In the original AD&D game, two unarmored (AC 10) 1st-level characters with no situational or ability modifiers have exactly a 50% chance of hitting*:

* In researching this, I found that 1st-level clerics and fighters have a 55% chance of hitting an AC 10 opponent in 1st Ed. AD&D, but stay with me here.

Much of this has to do with D&D’s origins in the original Chainmail, which was a wargame at the unit scale: given two opposing armies that were equally armed and armored, they had an equal chance of inflicting casualties.

Put another way: on a roll of 1-10, “you miss” and on a roll of 11-20, “you hit.” Might as well flip a coin. Where it becomes interesting is when there are modifiers that influence those probabilities. Things like:

- Strength bonus to overpower an opponent

- Dexterity bonuses to dodge

- Leveling up that improves the attacker’s skill

- Magical weapons that improve a blow

- Armor and shields that protect against attacks

- Spells that affect the performance of the participants

- Situational or environmental adjustments

This is where the chart becomes a tug-of-war: bonuses favoring the victim pull the odds towards a miss, while bonuses favoring the attacker drags them back in the other direction.

Your DM is already doing this in their head when a player makes an attack: taking the attack bonuses, subtracting the armor class, etc., and finding that threshold in the tug of war.

But before we get to the modifiers, though, what does it mean to miss?

Vagueness and Ambiguity

I was back to Gygax’s “avoided, blocked, parried, or whatever.” For our two unarmored, unskilled, unmodified combatants, a miss was just the tide of combat. Somebody swung and whiffed. Circling, they both psyched each other out and nobody did anything. A thrust was batted away.

This is Regular Melee Stuff. We don’t have any data on it, so it’s vague. Unquantified. Up to the DM.

(There’s Regular Melee Stuff on the hit side of things, too. You don’t have to be Cal Ripken Jr. to hurt someone with a baseball bat.)

However, once we start adding in modifiers, we actually do have some data. Those areas of the possibility space are ambiguous, and we can disambiguate it.

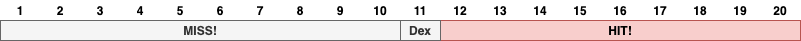

What if one of our combatants had a Dexterity of 15, giving them a +1 bonus to their Armor Class? That means an attacker misses on a roll of 1-11 instead of 1-10. On any miss, the DM could choose to spice up the encounter by citing the victim’s Dexterity. That’s cool; it’s playing a part in the combat and adding some color. The DM could assemble all the victim bonuses and all the attacker bonuses and pick one to attribute the outcome to. That seems totally reasonable, and you could stop there.

But what if we actually quantified that Dexterity bonus as part of our possibility space?

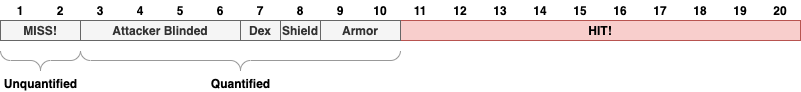

That gives us this:

A roll of 1-10 is still vague (Regular Melee Stuff), but if the attacker rolled an 11, we can attribute that miss to the victim’s Dexterity. The DM can now say:

“You take a swing that would’ve felled just about anybody else, but they were unnaturally quick, dodging your attack.”

If the victim had a Dexterity of 18 (+4 bonus), not only does it reduce the victim’s chances of being hit, but it also increases the probability that Dexterity is the reason why the attacker missed.

We’ve quantified the effects of the gameplay bonus. So the attacker will be hearing more and more frequently about how they keep missing due to the victim’s speed. And maybe that will cause them to change their tactics to reduce that advantage.

An Order of Operations for Modifiers

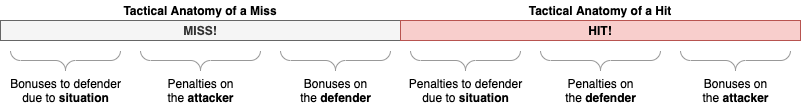

Most combats are going to have a lot of modifiers, because that’s what makes it fun. We could put the modifiers into any old order, which would be fine (probability will lead to the highest bonuses being attributed most frequently). But as I thought about it in terms of the tug-of-war, I looked at how I might map the possibility space to the intensity of the combat. Low rolls don’t approach the line of contention. As we move closer to a hit, things are getting more dangerous.

When I sat down to think about it, an attack is least effective when something external affects it. These are things outside of everybody’s control: the defender was behind a table, making it hard to hit them. We’re fighting on a slope. It’s the situation that benefited the defender.

Next up would be things in the attacker’s control that causes them to screw it up. They’re using a weapon they’re not proficient with. They’re swinging a broadsword with a Strength of 6. It’s their own damned fault that they missed.

Next in the order of operations are things within the defender’s control that actively improve their defense. They have a Cloak of Displacement on. They’re wearing a suit of plate armor.

Similarly, we can attribute successful attacks with an increasing intensity. Those just past the threshold are less intense than those deeper into the hit territory.

Here’s one way to visualize the order in which we apply modifiers to the possibility space:

We can go one step further within these broad groupings. When we think of bonuses to the defender, if I could avoid a sword thrust altogether, I’d do that before using my shield to block it. My last preference would be my armor. As we get closer to the line between miss and hit, we have to rely more and more on the factors that leave us the most vulnerable. If the DM tells me that the monster’s claws raked fruitlessly against my chainmail hauberk, that’s a signal to me that the monster had made it past my other defenses and was real close to tearing me to shreds.

Storytelling via Attribution

Hulla was part of a royal mission to deliver retribution against the raiders. She and her fellow marines landed at dawn, pulling their boats up onto the pebbly shore amidst a hail of arrows from the camp. The raiders’ priest was able to call down a bless on the defenders before the marines’ charge began.

Hulla spied the raiders’ leader and made a beeline for her. When the leader pulled out a glowing blue axe, Hulla threw a handful of sand into her face, blinding her. Nevertheless, the fearless raider bore down, threatening to slay Hulla with the axe.

Here’s what we have from a gameplay perspective:

Hulla is a Level 1 Fighter (no bonus to hit) with a Dexterity of 15 (+1 bonus to AC), wearing Leather Armor (+2 bonus to AC) and carrying a shield (+1 bonus to AC).

Tenderis is a Level 3 Fighter (+2 bonus to hit) wielding an Axe +1 (+1 bonus to hit). She is currently blinded for one round (-4 to hit) with sand in her eye. She is benefitting from a bless spell (+1 to hit).

Both fighters are on gravel, incurring a -1 AC penalty.

Tenderis is attempting to attack Hulla.

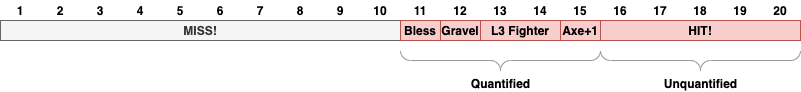

Here is how the DM has chosen to allocate the modifiers for Hulla’s defense:

A roll of a 1 or a 2 is a miss anyone could make, and the DM will have to make up a reason for it: Hulla parries, or Tenderis is distracted by an arrow flying close to her head.

A roll of 3-6 is a miss attributed to Tenderis’ blinding. The DM might use this as a storytelling moment for Tenderis to declare a blood oath against Hulla, or to call to her aides for support.

A roll of 7 is dodged due to Hulla’s above average Dexterity. The DM could straight up tell the player this to help reinforce the game mechanics’ role into the story.

An 8 means Tenderis missed due to Hulla’s shield. The DM can tell the players that Hulla’s shield absorbs the blow, directly tying the player’s equipment choice back to the story.

A 9 or 10 means Hulla’s armor is what saved her from being hit. With this system, the DM can inform players of what would have happened were it not for this modifier: this is the last bulwark between safety and injury.

And here is how the DM allocated modifiers for the attack:

A roll of 11 hits due to the bless spell in effect on Tenderis. The DM put this first because it was the deciding factor between a hit and a miss, adding dramatic value to the blessings of the gods. Spells like bless and prayer are often lost in the shuffle in normal combat.

A roll of 12 is a hit because Hulla is on shaky ground: she slips or overextends herself.

Rolls of 13 or 14 are ascribed to skill that a Level 3 Fighter has, focusing on what sets them above an average combatant.

A roll of 15 will owe its benefits to the magical axe +1. Perhaps it glows a vibrant green as it strikes true to compensate for its wielder’s blindness. The DM could have just as easily moved this to earlier in the queue (similar to how the bless spell made all the difference), but they chose to rank it higher to stress its deadliness.

16 or above is Regular Melee Stuff: the DM has to invent something here, but by and large we’re looking at Hulla being unable to get out of the way of the axe.

This example had the exact same odds as our two undifferentiated equals: a 50% chance to miss, a 50% chance to hit. But here we showed how the DM has context to make a compelling storytelling moment in what otherwise might be a boring tit-for-tat exchange. This could be especially useful in a CRPG that lacks the spur-of-the-moment improvisation that a tabletop DM can offer.

Depending on the style of the campaign, the DM might even hand the storytelling reins over to the player:

“Tenderis’ attack is going to be stopped by your shield. How does it play out?”

“I plow into Tenderis with my shield, binding her axe before she can swing. Did I knock her over?”

“Don’t push your luck. She holds her footing, but I’ll have you both in close combat next round.”

Tactical Studies: Rules

In the last example, we saw the player try to talk their way into a combat advantage after executing a shield rush. The shield rush was a storytelling moment invented because the enemy’s attack roll indicated a miss that was attributed with the defender’s shield.

This idea intrigued me, so I started to think about how the combat situation could change based on attribution. I’ll talk more about my ideas for how to handle a hit in the next post, where I want to re-evaluate how I think about hit points, but misses offer opportunities for tactical shifts as well.

From a tactical perspective, a miss could benefit the attacker, the defender, both or neither. Its usage is really up to the type of game the DM wants to be running.

If you are one of those terrible people who actually enjoys equipment degradation, attribution’s use is immediately apparent: the attack hit your armor, so we see if the armor is damaged or destroyed. This might be reasonable in a campaign heavily invested in realism, but for most this should probably be reserved for a moment of high drama. It’s punishing a player for not getting hit. On the other hand, this could be an equalizer for the 10th level fighter in plate mail being effectively invincible against an army of kobolds: while those kobolds will “miss” frequently, misses attributed to the armor could chip it away and eventually make that fighter vulnerable, adding a sense of believability to a game more grounded in realism.

In a real fight, people don’t stand in place trading whacks. The results of their attacks change the distance and the orientation. Boxers are forced to circle in order to avoid blows. Fencers back up to keep out of sword range. But we rarely see that in turn-based games: we move the miniatures into adjacent hexes and they tend to stay there until there’s a reason for them to move.

This may be where the “Regular Melee Stuff” comes in. A miss happened for something we can’t quantify: the defender dodged or used their weapon to parry, or the attacker made a mistake, or the combatants were interrupted by the rest of the melee around them. This is a careful line to tread: we don’t want every miss to result in the defender winding up with their back to the enemy–that just makes it feel random and un-fun. And if we put all of the tactical outcomes into the player’s hands, it could be min-maxed and abused. For now, I think tactical changes need to come down to a judgment call for the GM on what will make the game more exciting. A cop-out, but one I’m willing to own up to.

Circling Back

Let’s go back to the original goals and see how we did:

Make combat a more compelling storytelling experience. I hope I’ve illustrated how collecting evidence and attributing it to outcomes can lead to a more engaging experience. The DM has the information available to say what happened during an attack, or what would have happened were modifiers not in place. It can be compelling via dramatic narration and gameplay impact.

Have combat better reflect player choice in action and equipment selection so that it doesn’t feel disconnected and random. Even if you don’t stack-rank the modifiers and let the die roll dictate attribution, the act of collating the modifiers helps the GM (real or computer-based) to give combat results that feel grounded and less random. Minimal modifiers, like a +1 ring of protection, have opportunities to shine and reinforce how they add up to the bigger experience.

Make combat gameplay more engaging by expanding tactical outcomes and choices. I’m less successful here, as it’s hard to do tactical shifts and keep it balanced. There’s certainly opportunity for tactical outcomes. I hope that in the next article I can provide better material that links these more systemically.

Don’t add undue complexity or slow down the game. The referee is already doing these calculations, but often we’ve pre-collated them (e.g., the player has already boiled all of their bonuses down to a single AC value). The DM needs granular breakdowns. It adds some complexity and as a result slows it down some.